Congrats to PhD student Sevgi Demiroglu, who was recently featured in National Geographic Magazine for her anthropological research in Tana Toraja, Indonesia! The article, titled "A Closer Look: Sitting with the Dead" analyzes the Torajan practice of preserving the dead, to where deceased individuals are still a physical and active part of life. For Torajans, death does not truly begin until the funeral procession, which can occur many days, weeks, or even years after death. Congrats again, Sevgi! Find the article written below.

A Closer Look: Sitting With the Dead

"Saying goodbye to the deceased takes a while in the Tana Toraja region of Sulawesi, a lush, star shaped island in Indonesia. Here, death is part of life. When someone dies, the family mummifies them with formaldehyde and water and keeps them at home, where they are considered to makula', a sick person, whose soul is still present. The final stay in the house can last for years while a funeral is arranged, and during that time those still alive care for their family member; serve them food, tea, and cigarettes; and sit and chat with them.

This ancient practice is carried out despite the fact that most Torajans are Christian. It is a sign that Torajans embrace an eclectic mix of beliefs shifting between Christian worship and devotion to their traditional religion, Aluk To Dolo (Way of the Ancestors), which honors the god Puang Matua.

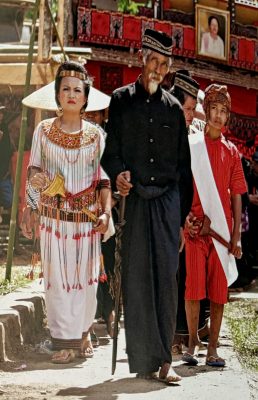

When the funeral called Rambu Solo- rites of descending smoke- finally takes place, it can stretch on for a week or more. The service is an amalgam of animistic beliefs and Christian practices, including recitation of the Lord's Prayer, all with the aim of ensuring the deceased successfully ascends to Puya, the realm of souls. There they become to'membalu puang, a person turned into a god. If the ceremony is not performed, the departed can become a bombo, a wandering soul. "The beginning of the funeral ceremony is the day that marks the declaration of the person's death, becoming orang mati, a dead person," says University of Connecticut doctoral student Sevgi Demiroglu, who is living in the village of Botang and studying the impact of afterlife beliefs and collective funeral rites.

Saying Goodbye

During the services, some hosts arrange for hairdressers to tend to the mourners, and families catch up with one another over coffee and tea. A few guests even look for romantic dates. Pigs are butchered for meals. There are also water buffalo. The grander the funeral, the more buffalo, with some mourners supplying the coveted blue-eyed pink skinned beasts called salepo. "We played Uno, uncles played poker, they drank plum wine, there is a lot of laughter," says Demiroglu of one ceremony she attended.

As the burial approaches, the body is taken from the home to a tongkonan, a structure with a sloped roof that calls to mind buffalo horns. Speeches are delivered, with rituals often recited in the Toraja language, as men stand in a circle and chant about the life of the deceased. The buffalo are slaughtered, and the meat is distributed to guests. "People have really creative ways of incorporating the tradition and current affiliation with major religions," says Demiroglu. The coffin is then hoisted to the tomb, at which point it is believed the deceased's spirit is taken by one of the buffalo to Puya.

Every few years Torajans also take part in the ma'nene' ceremony, where families bring the dead food, clean them, apply makeup to their faces, and occasionally take them out for an enjoyable motorcycle ride." (“A Closer Look: Sitting With the Dead.” National Geographic Magazine, 2025.).

Citation

“A Closer Look: Sitting With the Dead.” National Geographic Magazine, 2025.